Driving Techniques: The Racing Line

Anybody can drive a car quickly down a straight. All it requires is for you to point the wheel ahead and floor the throttle. But the overall quickness of a car is determined by how fast and smoothly a driver takes corners. Too many new, casual drivers put an unhealthy emphasis on engine power and straight line speed, thinking that a powerful engine will get them ahead on track days. Then when they find a more experienced driver getting ahead and pulling away in a smaller car, they wonder what is going on. Here’s the basic low-down on getting through a track corner quickly.

Anybody can drive a car quickly down a straight. All it requires is for you to point the wheel ahead and floor the throttle. But the overall quickness of a car is determined by how fast and smoothly a driver takes corners. Too many new, casual drivers put an unhealthy emphasis on engine power and straight line speed, thinking that a powerful engine will get them ahead on track days. Then when they find a more experienced driver getting ahead and pulling away in a smaller car, they wonder what is going on. Here’s the basic low-down on getting through a track corner quickly.

Before we dive in, there are a few concepts that need to be understood:

This is pretty much self explanatory. Smooth, sweeping turns are much easier to negotiate than tight hairpins and right angled kinks. The easiest turns are not even really turns, but the sweeping curves that are present on almost all public roads and long highways.

Use the whole width of the road to make any turn as wide as possible. This increases the radius of the turn to the maximum possible, allowing you to turn the steering wheel as little as possible and hold as high a speed as possible through the turn. Whenever you see a real track race, be it Formula 1 or GT racing, all the cars seem to line up in a straight line on the far side of the road when entering a turn. It is the fastest way through it, and there is simple no faster way through a turn.

3. This is why if the turn precedes a very long straight, the driver will position his car to be able to straighten out and get on the throttle as soon as possible, even before the car is through the whole turn.

Now let us examine the quickest way through a turn.

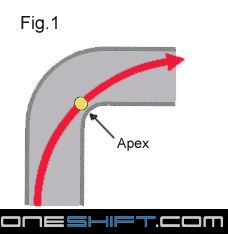

The basic line through a turn is known as the ‘out-in-out’. This refers to the line taken, where you start on the outside of the track cut across to the inside at the apex of the turn, then swing back to the outside. This line requires the least steering movement, and keeps the car as straight as possible, allowing it to go through the turn with the least amount of braking. Figure 1 illustrates this basic line. You will notice that professional drivers in touring cars and Formula 1 use as much of the road as possible to widen it, often running onto the rumble strips (the red and white sections bordering the track) at the entry, apex and exit.

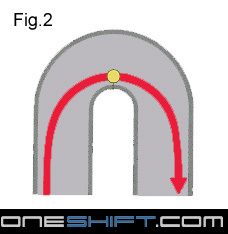

Figure 2 illustrates the racing line through a classic hairpin turn. Notice that if we were to drive in the center of the road through the whole turn, we will have a much more acute angle to turn through. By using the whole width of the road, the angle of the turn is lessened.

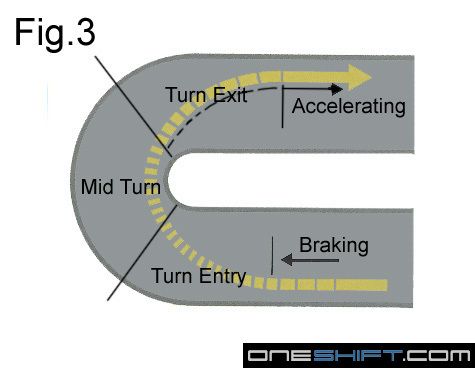

Every turn can be broken down into three sections (Fig.3), and in a true racing vehicle, how the car behaves in each section can actually be tuned individually. As you approach a turn (using the classic out-in-out line), you time your braking so that you will start turning the steering wheel at the exact point you reach the optimal entry speed. Aim for the apex by looking at it, and aim to clip it at a tangent. The point where you enter a turn is the turn entry. Here, the car is in a transition phase from its relatively unloaded straight line of travel into a side load. The car will begin to lean to the outside of the turn, applying load to the two outer tires. Compression damping of the shock absorbers are one of the main factors that determine how the car behaves as it begins to lean over in the turn entry.

The middle of the turn is where the car is committed to its line. At high speeds in this section, the outer wheels are fully loaded, the suspension is compressed almost fully, tires are at their limit of grip as sideways forces pull at the car, and if set up right, the car holds the line it was pointed into. Any attempt to wiggle the steering or drastically change the driving line now will upset the balance of the car. This is also the slowest point of the turn.

After clipping the apex, we start to lean on the power and aim for the outside of the turn. This is now the turn exit. The aim here is to keep the car pointed as straight as possible so that we can accelerate as quickly as possible. A turning car cannot accelerate as fast as one pointing straight, because a car still in a turn has more sideways forces pulling at it. In the turn exit, steering input is gradually eased off as the car powers ahead, and the sideways load on the tires are easing off. On the drive wheels, acceleration forces start to take over. The car will also start to ‘stand up’ as the suspension brings the car back into an upright position, out of the lean. How quickly the car returns to the neutral suspension position depends a lot on how the rebound damping of the shock absorbers are tuned. Slow rebound damping will make the car sluggish, making it slow to ‘stand back up’. In a series of turns, this will cause instability issues. If the rebound damping is to fast, the car might kick back upright too quickly, and feel like it takes a hop as it exits the turn.

After the turn exit, the car is considered as having fully exited the turn, and can power down the straight to get in line for the next turn.

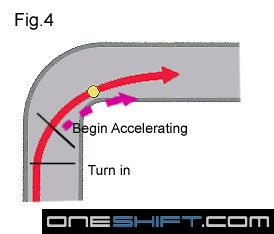

Figure 4 shows a classic late apex line, where we turn later, and clip the inside of a turn later than the real apex. This sacrifices a little speed at the entry for an extremely quick exit. You can see that we turn later and sharper at the entry, requiring us to enter the turn slightly slower. By taking a sharper entry and aiming for an apex clipping point later than the classic textbook maneuver, the rest of the turn becomes much straighter. As illustrated in Fig.4, we can start accelerating even before we reach the clipping point, as most of steering has already been completed 1/3 of the way into the turn.

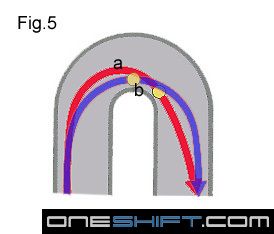

This is sometimes called the high line, because when compared against the standard way of taking a corner, we go higher and deeper into a turn before actually turning. Figure 5 compares the high line against the classic driving line. The driver taking the red line can start accelerating by Point ‘A’, but the driver on the blue line can only start accelerating at Point ‘B’.

The high line is taken mainly when the straight following the corner is a long one. By using a later clipping point, you lengthen the straight as much as physically possible, and can start accelerating before you are even halfway through the turn to build up as much speed for the straight. On a racing circuit when two cars are entering a turn side by side, the car on the outside line can easily overtake the car on the inside with this maneuver if there is enough room at the turn exit. The car on the outside line will give the advantage to the car holding the inside at the turn entry, allowing him ahead. Then by taking the high line, the outside car can accelerate quicker and take a straighter line out of the turn, cutting to the inside at the turn exit while the car originally on the inside line runs wide and accelerates later.

How does all this relate to real world driving? There are lessons here that are very useful in interstate driving, especially in countries with long, winding highways and blind corners.

Learn how to aim your car as you drive through blind corners on desolate interstate highways, especially in places like the USA and Australia. For such applications, the late apex turn is the most practical approach as it lets you see as far ahead as possible while keeping your car under control. Unlike Singapore, interstate highways tend to have wider lanes than urban road. This is to take in account that trailers, trucks and road trains use these roads on a daily basis to transport cargo between states. These wider lanes allow you to stay within your lane while smoothing out the curves as much as possible.

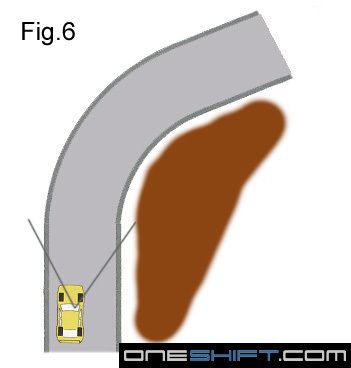

Let us take for example, a blind right hander (the turn goes around the side of a cliff) coming up on a one-way, single lane road. We would move a little to the left side of the lane we are driving in, and then slow down smoothly to turn in. When we take a late apex, we can see what is around the corner much earlier, allowing us to spot any possible problems round the corner. The question is, when on the road, how do you know when to ‘clip’ the inside of your lane? Set a clipping point only when you clearly see the exit and can accelerate smoothly. The following sequence shows a car on an empty, one way road going around a hillside. The driver cannot see around the corner and does not know what to expect. In Figure 6, he is approaching the corner, staying more to the outside.

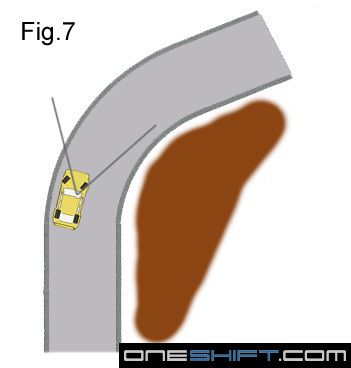

In Figure 7, he has started to turn while still staying to the outside to allow him to see round the hill at the earliest opportunity.

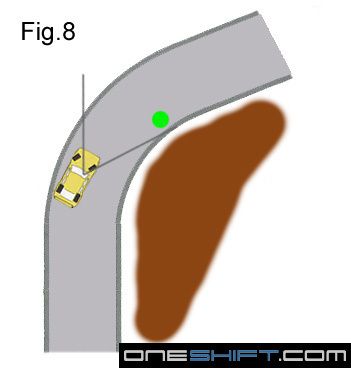

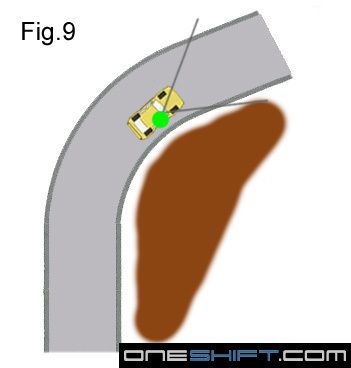

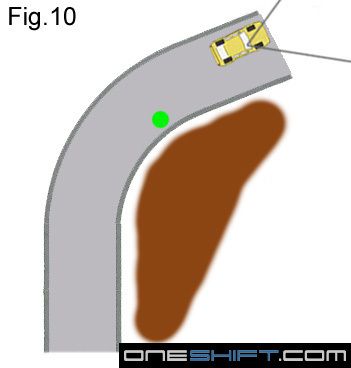

By Figure 8, he can clearly see around the hill and sees no signs of danger. He sets an apex, and follows through smoothly in Figures 9 and 10.

Note that such an approach should only be safely done when there is no other traffic around you for maximum safety, and you must stay within your lane at all times! The sideways movements have been exaggerated in the images for clarity.

In a more urban context, the classic ‘out-in-out’ line can be subtly used to take sharp, right angled corners on public roads when there is no one in the lane immediately next to you or approaching you. But remember; keep the movements subtle as there is no excuse to be driving out of your lane. Even a subtle movement will give you a smoother line, and reduces the likelihood of hitting the sharp corner of the kerb that often juts out into a point where the two roads meet.

Credits:

Get the Best Price for your used car

from 500+ dealers in 24 hours

- Convenient and Hassle-Free

- Consumer Protection

Transparent Process

With No Obligation