Driving Techniques: The Heel & Toe.

In these days where automatic transmissions are everywhere, the heel & toe technique has become something that is practically unheard of amongst casual drivers. Many boy racers claim to have heard of it; some claim to know what it is, but very few daily drivers really understand the mechanics of it. How is it done?

In these days where automatic transmissions are everywhere, the heel & toe technique has become something that is practically unheard of amongst casual drivers. Many boy racers claim to have heard of it; some claim to know what it is, but very few daily drivers really understand the mechanics of it.

“What’s that? Some kind of dance move?” some might ask. No it is not. It is a method to quickly downshift and maintain stability of the car at high speeds and high revs through a turn, while allowing for a smooth and quick acceleration out of it. It is practiced exclusively by race drivers everywhere because it is the fastest way to get into gear and brake at the same time. Before the advent of synchromesh gearboxes, heel & toe as well as double de-clutching were necessary skills to be able to drive a car.

Before we begin, there are some fundamental characteristics of taking a turn at high speeds that we need to understand:

Do not coast through a turn. Even worse, do not coast through a turn with the clutch depressed! A freewheeling car is a dangerous car. Especially when in a long, fast turn, centripetal forces and all manner of laws of physics pull at the vehicle and threaten to destabilize it. Keep your foot on the throttle when cornering, but you do not have to speed up. Hold a constant speed with a light touch. The idea is to keep power going to the drive wheels so that the car is being pulled (or pushed in a rear wheel drive car) in the correct direction, and not simply rolling along.

This does not always hold true for a well tuned racing car that has been adapted to the surface, but in a regular vehicle, braking while turning at high speeds can have disastrous consequences. In simple terms, when the brakes are applied hard, inertia will continue pulling the car in the last direction of its travel. When driving straight, this is not a problem. But if your start entering a corner, find that your speed is still too high and apply the brakes while the wheels are turned, the laws of physics dictate that inertia will pull your car straight on. Not in the direction of where your front wheels are pointing, but straight ahead and off the road. When entering a turn, the tires are already stressed from centripetal forces. Applying the brakes now will only stress them further and they may break traction. Some drivers might have already a habit of braking through a turn, and experienced the strange feeling when the car unbalances and wobbles in a strange manner. “But I have anti-lock brakes!” some may exclaim. Anti-lock brakes are there to make up for human error and panic responses when drivers jam hard on their brakes. Knowing how to modulate your brake pedal is a skill. It can only benefit you when you learn it well.

When exiting a turn, power out as smoothly as your tire grip allows. Smoking your tires out of a turn is a waste of power. Spinning tires don’t push you forwards (unless you are practicing your drift technique); they are rolling on the spot. Power out too hard, and a front wheel drive car will understeer while a rear wheel drive car tends to oversteer or even spin around completely.

Now that we have that out of the way, here is why heel & toe is effective when cornering at speed on a closed circuit: it gets you into the correct gear for the turn and exit without compromising braking, stability, or entry speed. It also keeps the engine revving in it's optimal power range (attempting to balance a half clutch while halfway through a corner is ineffective, and accelerating from near engine idling speed is all but useless) This is the basic form of how it is carried out:

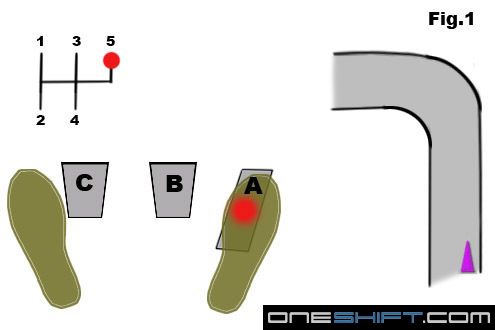

In Figure 1, we are approaching a left turn on the track at the end of a long straight. The right foot is planted firmly on the accelerator. The car is in fifth gear and high on the engine revs.

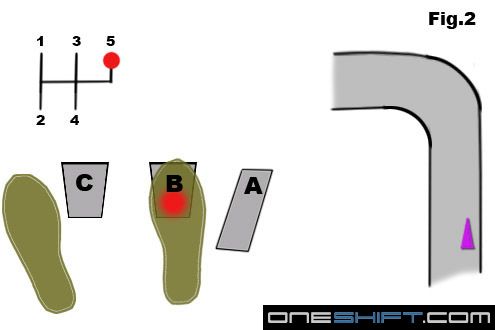

In Figure 2, we begin to brake (braking distance is shortened in diagram for compactness).

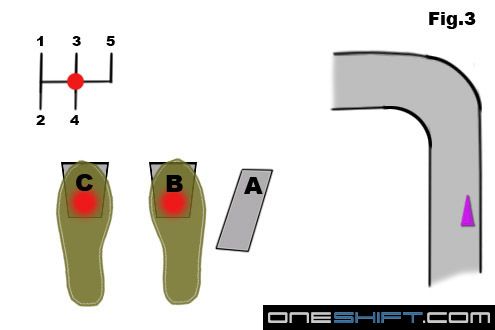

In Figure 3, we prepare to downshift. The turn will be taken in third gear. The right foot is still on the brakes, slowing the car to the optimum speed for entry. The left foot has depressed the clutch and the gearshift has been taken out of fifth gear.

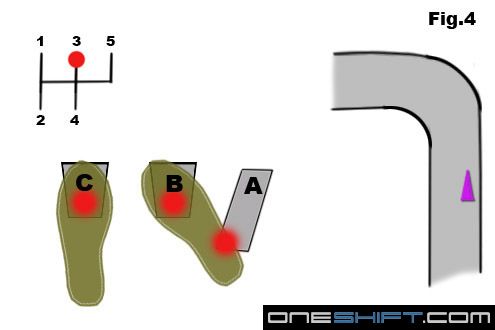

Figure 4 shows the crucial step. While still under braking, the right foot rotates to blip the throttle with the heel. This is the reason why the accelerator pedal is always longer than the other two pedals. This move is also where the maneuver got its name. At the same time, third gear is selected.

The throttle is blipped to match revs when the clutch is released. If the clutch was released into third gear without blipping, the engine speed will be too low, resulting in that sudden jerk so familiar to learner drivers. At high speeds this could lead to a spin out. How hard the throttle needs to be blipped comes with experience in the car and knowing how high an engine speed is needed for that particular gear at that particular speed. When done correctly, you will hear the engine note rise and the gear can be dropped in smoothly all while still braking.

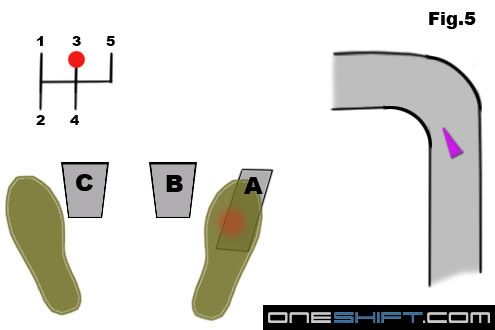

By Figure 5, the car is at the correct turn entry speed, the clutch has been released into third gear, and we are turning towards the apex of the turn. The throttle is feathered lightly to stay on the power, but not pushing for more speed.

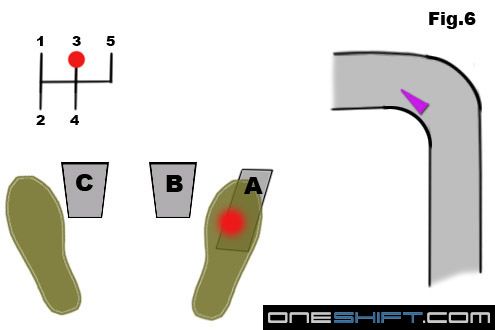

In Figure 6, we are past the apex and heading for the turn exit. We can increase power smoothly now to get through the turn and accelerate through to the next straight.

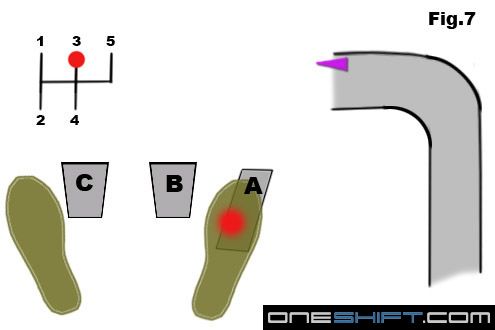

In Figure 7, we are clear of the turn. By now the engine should be close to redlining third gear. Your in-car waltz for this turn is done. Grab fourth gear and power ahead to the next turn, where the process begins again.

It looks like a long series of steps, but in practice, Figures 4 to 6 take place within half a second. What you will notice about this is that at no time during the turn is the car freewheeling. As it approaches the turn, it is braking and using that same period to get into the correct gear to push out of the turn. By the time we are entering the turn (Figure 5), the car is already in the correct gear and pushing through the turn. At no time is the car freewheeling or being unbalanced by other maneuvers while in the turn.

Novices often think that straight line speed is more important than agility, but consider that on a closed circuit, you spend up to 70% of a lap time in the turns. The driver that carries the most speed through a turn and exits the fastest gets ahead, and carrying speed through a turn is more that about engine power. Diving as fast as you can headlong into a turn is also an invitation for disaster, because more often than not, you’ll find yourself going too fast and unable to turn tightly enough. The result is you desperately brake halfway into a turn, ruining the car’s momentum and upsetting the balance. That is why there is the old racer’s adage, ‘slow in, fast out’. Enter a turn slow, setting up for the exit, then accelerate quickly and smoothly to clear the turn once past the apex.

Stay tuned for the next article, where we will talk about racing lines, why they are effective, and how they can sometimes be applied in real world public road conditions.

Credits: Lionel Kong

Get the Best Price for your used car

from 500+ dealers in 24 hours

- Convenient and Hassle-Free

- Consumer Protection

Transparent Process

With No Obligation